Growing Community in Blackford County

By: Contessa Hussong

There’s an old saying that the Midwest has 13 different seasons.

Don’t like the weather? Wait an hour. It’s sure to change.

Yet despite the calamity of Indiana weather, small farming businesses are thriving. The farm-to-table concept is growing deep roots in Blackford County as farmers provide not only for their own families, but for those in need.

Shane McNeal of Colanna Homestead Farms is one example of that success. Though he’s only been gardening for the past three years, McNeal has found a passion for both produce and people — and his business is growing because of it.

“[We’ve] just steadily been trying to get bigger each year,” McNeal said. “We took a big step this year, bought two 100-foot greenhouses . . . and then we have two 50-footers as well.”

The figures demonstrate the effort McNeal pours into his practice, despite working on his own, especially after his two children, now adults, have moved on from helping him tend the gardens.

McNeal’s children, Cole and Brianna, are the inspiration for Colanna’s name, and McNeal started the business to spend more time with them. As they’ve grown up, however, McNeal has come to realize connecting with family isn’t the only form of community his farm offers.

As regular customers come in, McNeal has learned to grow produce with specific customers in mind, whether that means growing low- or no-acid tomatoes or customer-requested sweet fennel.

Of course, he’s also mindful of his neighbors.

“There’s a gentleman in town I’ve been friends with,” McNeal said. “My places to set up are right next to him. I don’t want to compete with that . . . . He can’t get out and do this stuff he used to do, so why compete with his only income?”

McNeal grows a little bit of everything, from potatoes and poblanos to green beans and okra. But he’s remained flexible, willing to cater to his customers as he gets to know them.

“I’ll custom grow anything,” he said. “I immediately go look for the seed and I will have it for them next year. So, I just try to grow. I want to stay in Blackford County.”

This is where he’s put down his roots, much like Dustin Slaven, who with his family runs both the Slaven Homestead in Hartford City and Gerber Locker, located in Craigville.

Slaven has been in the butchering industry since he was 18, although, like McNeal, his homestead is a newer development. The Slavens bought their farm roughly two years ago, and acquired their slaughterhouse in May.

For the Slavens, too, farming is a family affair.

“It’s the greatest thing of this work,” Slaven said. “[My kids are] included in everything. They have helped anywhere from building fences, [to] building chicken tractors when we raise our meat chickens . . . . My 11-year-old daughter, she can pretty much handle a knife with the best.”

Farming has also allowed Slaven to get to know his neighbors better. One interaction that began with Slaven buying two cows off a man down the street has turned into a friendship, and a relationship Slaven developed with another homestead led to mutual support between the two businesses.

Put simply, farming in Blackford isn’t competitive, it’s collaborative.

“I think through having a small business and a small farm, you know, we try to support local businesses as much as possible,” Slaven said, “and I don’t think there’s anything greater that you can do.”

It’s a point McNeal echoed as well. After all, why live in conflict when one could live in community?

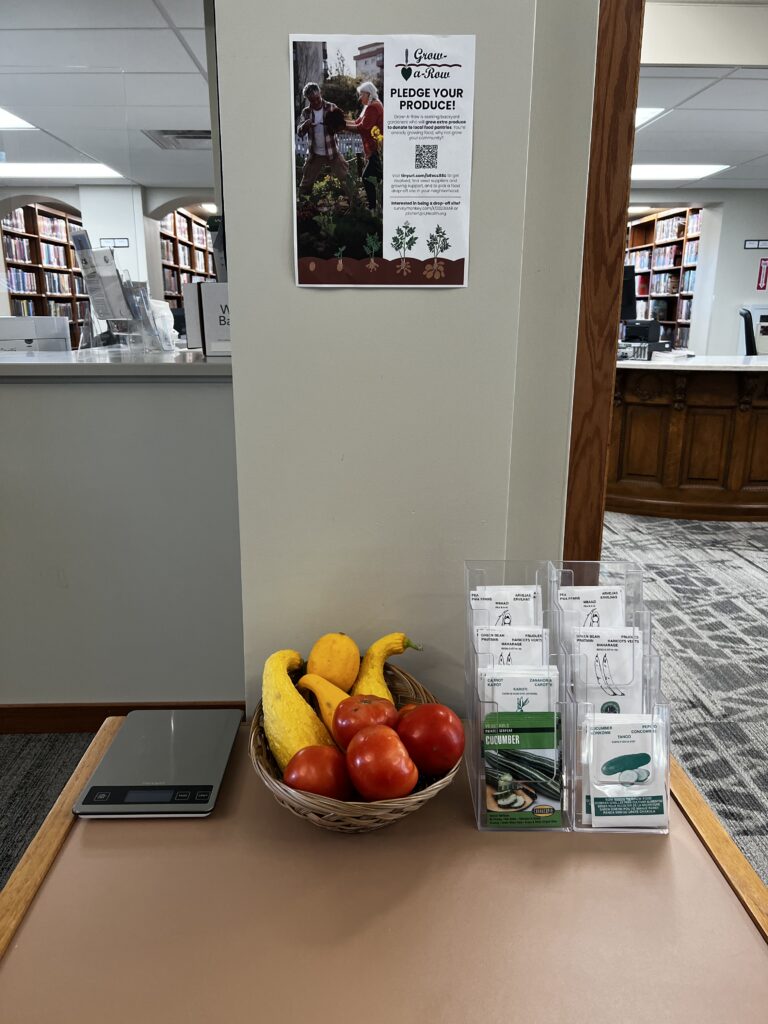

It’s this community mindset that has led to the development of Grow-a-Row, a small but expanding program that encourages locals to grow extra food in their gardens with the purpose of donating it to their neighbors in need.

From each designated drop-off site, fresh fruits and vegetables are put into the hands of those who may not otherwise be able to afford them.

The program is only in its second year, but for Lindsey Cox, the community wellness coordinator at Purdue Extension, and John Disher, director of community outreach for IU Health’s East Central Region, it’s a passion project — something they knew they needed in their respective communities.

“If you look at a place like the YWCA of Muncie, or if you look at the food bank there in Hartford City . . . those food donations or canned items, boxed items, they are not fresh produce,” Disher said.

Grow-a-Row seeks to change that. Last year, the organization partnered with 13 locations in three counties, their Blackford location alone gathering 800 pounds of produce.

This year, they’ve added a new location in the Hartford City Public Library.

“We didn’t want to manage some kind of intricate program,” Cox said. “So, we worked with partners that we already have or know about in the community and asked folks if they would be willing to be collection sites essentially for this donated produce, as well as distribute it to the folks that they’re serving.”

With 5,000 to 6,000 pounds of produce distributed last season, the program is already starting to leave an impact, making connections much the same way as McNeal or Slaven.

It’s true, the weather in the Midwest can change in an instant. But intentional service, intentional community, and intentional farming are as steadfast as the sun setting over an Indiana cornfield. Farming in Blackford County is about more than simply putting food on the table. It’s about pulling up a chair and getting to know the people who depend on our farmers every day.